Similar to its architectural meaning, the state-led program of rustication called for aesthetic techniques of surface treatment—for turning the outward appearance of urban, usually Han, subjects into rural working bodies. However, this process of urban-to-rural resettlement produced real physical and psychological attachments to land and labor. The distinct category of “educated youth” (zhiqing) enabled the state to target a model population of young (aged 16 to 25 sui), urban, and able-bodied subjects for spatial migration. These individuals cultivated new landscapes and engendered a new socialist subject for the nation. Yet, the construction of this subject—and their identification by the state—revealed epistemic rifts between the migrant and native “ethnic” bodies working in the PRC’s “peripheral” landscapes.

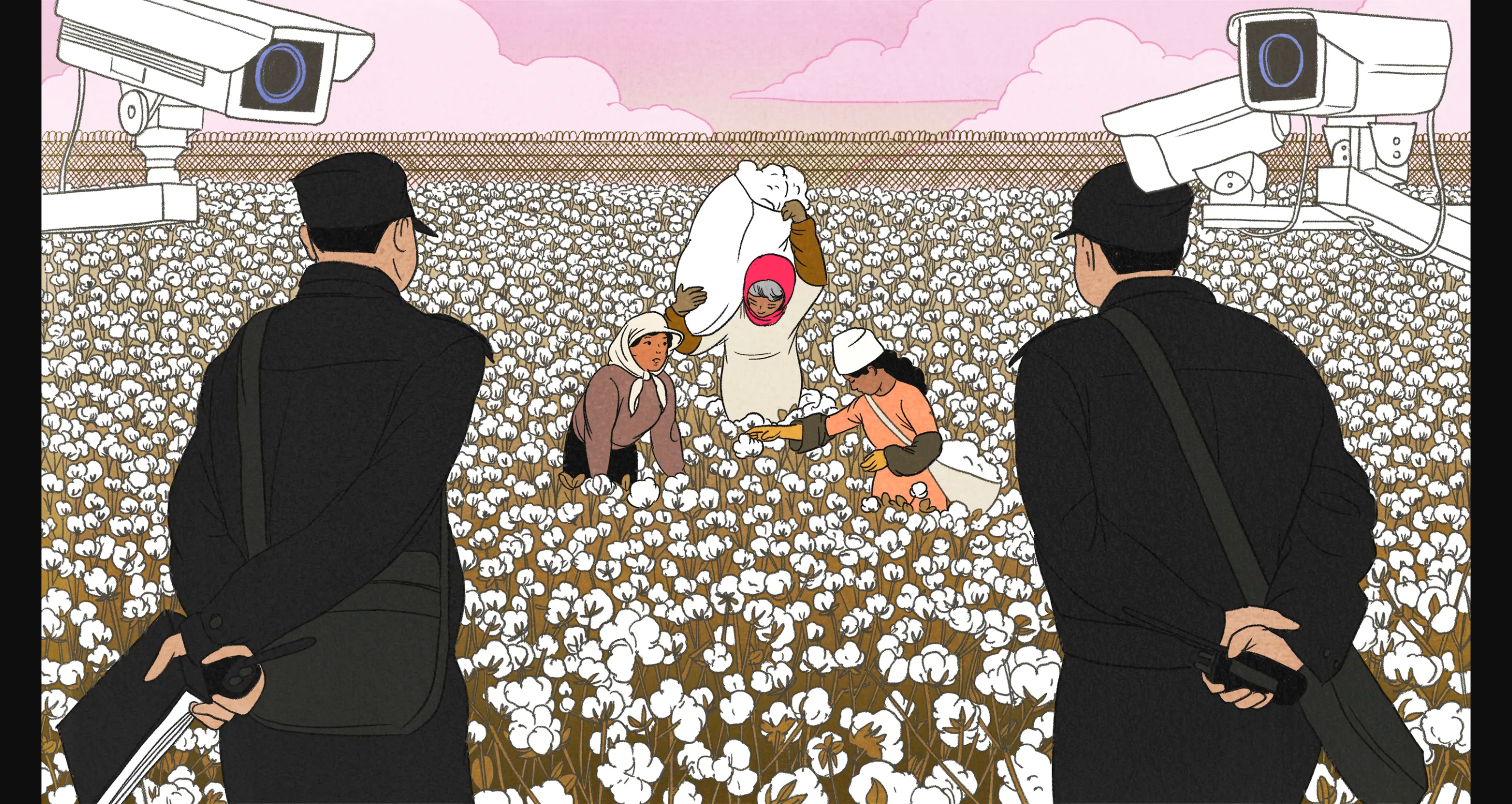

The militarized state mechanism of the Corps engendered what the Xinjiang “countryside” meant for foreign migrants: it put them to work, and many stayed permanently. However, the Corps also absorbed Uyghur, Kazakh, Turkic and Soviet labor. How were these working bodies imagined and constructed to maintain the model socialist subject? How did they (dis)identify with the subject position from which they were summoned by the state? While the settler logics of Sinification offer a crucial framework for examining state violence, this approach often makes legible a model Han subject, against whom the “ethnic minority” is pitted. By attending to the everyday and relational conditions between the working bodies enclosed within the XPCC’s environments of cotton, I hope to recover the ordinary terror and embodied life of working bodies producing Xinjiang cotton in the margins of Chinese empire.

This research will draw on recent scholarship, census material from China’s Population Yearbook, state media (e.g., newspapers such as Renmin Ribao and Xinjiang Ribao), and digital approaches to inaccessible or limited sources. I will focus on the early work of the XPCC in the Manas River Valley, mapping the historical farms and fields in and around the present-day city of Shihezi. The divisions of the XPCC will serve as an organizational entry point into historical sources and collecting the necessary information for building datasets. The form and format of the final project will be an interactive and narrative webmap that will communicate the outcomes of this work.

While present-day issues around “Xinjiang cotton” are well-documented, its history has been far less examined, particularly in the US. Ultimately, this project launches a historical investigation in order to carefully redress the mass detention and policing of ethnic populations, largely Uyghur, and the allegations of their forced and slave labor on Xinjiang’s cotton farms. The political necessity of addressing the structural dimensions of this settler, colonial, and imperial violence and its globalized idioms of power cannot be understated. Nonetheless, Xinjiang’s heightened visibility is often summoned to maintain a US-led global order. The predicaments of this optics of visibility—of what is absented in presence—propels the larger political project of my research. I hope to find who remains in that excess.